CLEP – The interconnected challenges of the 21st-century global economy necessitate a reevaluation of competition law systems worldwide in the spirit of multidisciplinarity. It means not only reviewing in light of its intellectual roots in jurisprudence, microeconomics, and ethics, but also recognizing the rapidly increasing number of valuable insights from contemporary studies on information and complexity. This blog post marks the beginning of the Competition Law, Economics, and Philosophy series, which will comment on this process. It will be a mix of these three disciplines, seasoned with a bit of literature, science, technology, and personal experience.

Who understood competition better –

Adam Smith or Charles Darwin?

I read many years ago some books on political economy, and they produced a disastrous effect on my mind, viz., utterly to distrust my own judgement on the subject and to doubt much everyone else’s judgement!

(Letter from ChD to ARW, 12 July 1881)

File: SSRN

The Greatest Economist and His Competitor

When asked who the most outstanding economist who ever lived was, many people will intuitively point to the famous Adam Smith, the founding father of this discipline. On the pages of his three great treatises (TMS, 1759; LJ, 1763; WN, 1776), we can find analyses of the complex society emerging before his eyes and valuable postulates for increasing the role of competition in it. This work largely overshadowed the achievements of even the greatest earlier economists, such as Richard Cantillon (1775) and Francis Quesnay (1758). Further economic elaborations of this scale and quality were brought only in the following century by David Ricardo (1817), John Stuart Mill (1848), and Karl Marx (1867). Each of them emphasized Smith’s crucial role in inspiring their theories. His achievement surpassed that of his predecessors, and those who followed paid him a well-deserved tribute. Given this, it is difficult to imagine anyone who could fight with him for the title of the thinker who best understood how competition — the fundamental market process — works.

Adam Smith’s apparent monopoly on being called the prophet of competition often comes from the narrow perspective usually adopted. The only other contenders considered besides him are the great nineteenth-century economists over whom he had the first-mover advantage. This view ignores other scholars who analyze competition to understand this phenomenon from a broader perspective, going beyond the market investigations. It’s particularly unfair to non-economists whose achievements have influenced the development of “the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses” (Robbins, 1932). Without a doubt, the most important of them, and the only one who can rival Smith, is Charles Darwin, who founded the scientific theory of evolution. In recent years, this name has appeared frequently in texts on competition economics (and law!), especially those of the rapidly developing initiatives, I shall describe here as “complexity-minded competition policy” (e.g., CLES; DCI; IIASA; AIA). In the author’s opinion, understanding the competition process in the modern, complex economy is not about putting one thinker above the other, but about comprehending their shared history and interdependence.

The Evolutionary Theory and Her Fathers

The year 2023 was particularly important to lawyers interested in research on competition and its development. First of all, it was the tercentenary of Adam Smith’s birth, celebrated in the economics departments all around the world. Those aware of the Smithian definition of political economy and his obscure treatise, Lectures on Jurisprudence (1763), celebrated this anniversary as equally significant to legislators and lawyers. Another reason for celebrating this year (especially for the latter) was the publication of two academic articles developing a new paradigm of competition policy based on the science of complex adaptive systems. The first article was co-authored by Nicolas Petit and Thibault Schrepel, and another proposal to apply complexity science to competition law came from Ioannis Lianos, who has been publishing on this topic since 2018. Thanks to Darwin’s analysis of the interaction between species and their environment, many recognize him as a precursor of this scientific perspective. One could then assume that the focus on complexity will draw these two publications away from Smithian classical political economy vision of competition toward evolutionary studies. However, this post argues that the increased interest among competition lawyers in complex adaptive systems does not compromise the authority of Adam Smith’s theories. To understand this, it is worth first taking a look at Darwin’s correspondence with his close friend and ‘rival’ in the race to conceive the scientific theory of evolution.

In 2023, we also celebrated the round anniversary of another great scholar’s beginning. It was the bicentenary of Alfred Russel Wallace’s birth. This English naturalist, independently of Darwin, conceived an exact scientific theory of evolution. Darwin learned about it from the 1858 letter Wallace sent him, while pursuing his research in the Malay Archipelago. Subsequent events demonstrate not only the genius of these two scientists but also their intellectual honesty. In the very same year, Darwin organized a joint presentation of their insights in the form of a co-authored article to the Linnean Society of London. And a few years later, Wallace wrote him: “As to the theory of “Natural Selection” itself, I shall always maintain it to be actually yours & your’s only” (1864). The correspondence between these scientists continued until Darwin’s death. He sent the most interesting letter from this post’s perspective less than a year before his passing.

In 1881, Wallace sent Darwin a recommendation of Henry George’s Progress and Poverty (1879): “It is, the most startling novel and original book of the last twenty years, and if I mistake not will in the future rank as making an advance in political and social science equal to that made by Adam Smith a century ago.” Darwin’s answer is decisive evidence of his interest in early economics: “I read many years ago some books on political economy, and they produced a disastrous effect on my mind, viz. utterly to distrust my own judgment on the subject and to doubt much everyone else’s judgment.” Regardless of how we interpret this quote from Darwin. Whether as a rebuke to the political economy, he was familiar with, causing him to be extra cautious about the further development of this discipline. Or as praise for it as opening his eyes wide to the relative nature of judgments. The fact remains that classical political economy played a significant role in Darwin’s intellectual development.

To write that classical political economy was not indifferent to the early theory of evolution is a vast understatement. Darwin’s research drew inspiration directly from the specific achievements of various eighteenth-century economists. For him, the most important was Thomas Robert Malthus’ work (1798). Still, in the first scientific theory of evolution, one can also find references to Bernard Mandeville (1705 & 1714), David Hume (1739), and Adam Smith (1759 & 1776). Darwin’s notebooks show that he had studied the classical political economists intensively and “drew upon them exactly when he had his own theoretical breakthrough on the conception of biological evolution.” The next section of this post presents, in chronological order, four thinkers of this century who contributed significantly to the theory developed by Darwin in the following century.

The Classical Economists and Their Reader

The path of political economy to gaining Darwin’s attention began in 1705 with the publication of the poem The Grumbling Hive. Its author, Bernard Mandeville, despite his lyrical work and medical profession, is remembered primarily as an economist. This happened thanks to a two-volume defense of this poem, published nine years later and known to this day as The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits (1714). In these works, Mandeville describes the morally decayed community of bees, calling their god, Jove, to end the vice. However, the fulfillment of the bees’ wish surprisingly leads to the rapid collapse of their society, as many professions and activities that underpinned it disappear. Mandeville’s contemporaries saw his poem mainly as a questioning of traditional morality. However, its most important part is the idea of a social order that did not rely on a central design to function, but rather on the individual actions of its constituents. Darwin adopted it into his theory that life creates order and change not because of a providential guiding force, but through its own existence.

Mandeville is a good example of how Darwin was primarily influenced by the early “complexity” economists, who had developed the idea of unintended consequences and an emerging “spontaneous” complex order arising from many decentralized individuals pursuing their self-interest over time, with no common intention or central deliberate design. As Fable of the Bees states, “some arts may be and have been raised by human Industry and Application, by the uninterrupted Labor, and joint Experience of many Ages.” Mandeville illustrates it with an example of the ship. He points out that no individual mind had conceived of that invention in advance, and even now, only a few could fully understand its operations. He comments on a book describing in detail and mathematically every mechanism of a ship: “I am persuaded, that neither the first Inventors of Ships and Sailing, or those, who have made Improvements since in any Part of them, ever dream’d of those Reasons.” Those reasons emerged from countless attempts by individuals who interacted to improve their seafaring opportunities.

It was probably Mandeville’s work, combined with Darwin’s experience meeting the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego, that prompted him to also use the ship metaphor in one of the most famous fragments of On the Origin of Species (1859). Due to its importance, this fragment deserves to be quoted in its full length:

When we no longer look at an organic being as a savage looks at a ship, as at something wholly beyond his comprehension; when we regard every production of nature as one which has had a history; when we contemplate every complex structure and instinct as the summing up of many contrivances, each useful to the possessor, nearly in the same way as when we look at any great mechanical invention as the summing up of the labour, the experience, the reason, and even the blunders of numerous workmen; when we thus view each organic being, how far more interesting, I speak from experience, will the study of natural history become!

The opening example of the ship in Darwin’s argument confirms what Friedrich von Hayek often emphasized. His work underlines that evolutionary biology inherited its founding concepts from classical political economists: “The idea of biological evolution stems from the study of processes of cultural development.”

Conrad Martens (1834). HMS Beagle at Tierra del Fuego.

From The Illustrated Origin of Species by Charles Darwin (1859).

The theory of the creative power of a simple “succession of events” was first presented by David Hume. For numerous reasons, this famous philosopher is also considered a classical political economist. Years before Darwin’s birth, his grandfather, Erasmus, emphasized Hume’s importance in Zoonomia (1794): “[H]e concludes, that the world itself might have been generated, rather than created; that is, it might have been gradually produced from very small beginnings, increasing by the activity of its inherent principles, rather than by a sudden evolution of the whole by the Almighty fiat.” Postulating this perspective, the philosopher and political economist directly influenced the development of Darwin’s evolutionary theory. The latter showed a clear use of Hume’s expression “succession of events” commenting in 1868 on what he had said in the Origin of Species: “I have … often personified the word Nature; for I have found it difficult to avoid this ambiguity; but I mean by nature only the aggregate action and product of many natural laws, and by laws only the ascertained sequence of events.” Hume, however, also influenced Darwin in another way, this time in collaboration with his longtime friend Adam Smith.

In his works, Darwin draws on the theory of human nature, which he borrows from the founders of political economy and the philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment. In Hayek’s views, Hume and Smith were “Darwinians before Darwin” and, more specifically, “Hume may be called a precursor to Darwin in the field of ethics.” Conceptions of order, as well as the mechanisms and the product of evolution, are then the consequence of Hume’s theory of human nature. Much influenced by Adam Smith, Darwin related the origin of the moral sentiments and the social instincts to evolutionary theory. He most frequently cites the classical political economists in The Descent of Man (1871), particularly Hume’s Treatise on Human Nature (1740) and Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). According to the perspective adopted by these thinkers, civil society was not created by a social contract. Human beings have never lived in isolation or separation from others. For Hume, the “very first state and situation” of man is a “social state” in which “cordial affection, compassion, sympathy, were the only movements, with which the human mind was yet acquainted” (Of the origin of justice and property). Darwin recognizes in this situation the evolution of morals: “any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts […] would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience.” Darwin’s Humean-Smithian inspiration was best summarized by Hayek in his research on that topic: “Man is not born wise, rational and good, but has to be taught to become so. It is not our intellect that created our morals; rather, human interactions governed by our morals make possible the growth of reason and those capabilities associated with it.”

The crucial way Smith influenced Darwin’s research was by formulating the principle of the division of labor. Around 1854, the biologist realized how this principle explained biotic diversification. In analogy to political economy, a diversified natural economy would support the maximum amount of life. As in economic competition, in the struggle for existence, different organisms are better at exploiting different resources, giving rise to a natural “division of labour” — a locution Darwin used five times. He emphasizes these analogies and points to his inspirations in the fragment of On the Origin of Species: “So in the general economy of any land, the more widely and perfectly the animals and plants are diversified for different habits of life, so will a greater number of individuals be capable of there supporting themselves.” In her 1980 article, Silvan Schreber states that “[W]hen he adopted […] Adam Smith’s insight into the competitive advantage of the division of labour, Darwin was aware that he was ‘biologizing’ the explanations political economy gave for the wealth of nations.” And modern evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould in his Structure of Evolutionary Theory (2002) agreed that Darwin’s theory “is, in essence, Adam Smith’s economics transferred to nature.” Also Milne-Edwards, who first applied the term “division of labour” to organisms (1834) and whom Darwin cited as his source for the idea, himself attributed the idea to “modern economists.”

Without diminishing how much Darwin owes to earlier political economists, Thomas Robert Malthus is considered to have had the most significant influence on him. In 1798, this English cleric published a famous Essay on the Principle of Population, portraying the economy as a competitive struggle for survival. According to the author, this struggle results from population growth outpacing humankind’s ability to increase productivity. Malthus did not regard this “principle of population” as novel. The Essay acknowledges that it had been stated previously by David Hume, Adam Smith, and “probably by many writers that I have never met with.” It doesn’t change the fact that the Malthusian “struggle for existence” became the basis of natural selection in the evolutionary process described by Darwin. He drew heavily on Malthus, whose work helped him, in the end, make the Darwinian model of evolution fully non-teleological.

Both founders of the scientific theory of evolution, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, were indebted to Malthus’ Essay on the Principle of Population for a crucial element in their independently formulated theories of natural selection. The former described it in detail in his autobiography: “In October 1838, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic inquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on, from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favorable variables would tend to be preserved and unfavorable ones destroyed. The result would be the formation of a new species.” The role of this economist in the development of Darwin’s work is best expressed in a statement made close to the end of this passage: “Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work.”

Already before, Darwin concentrated his evolutionary studies on competitive processes. But Malthus’s Essay shifted his attention from competition among species to competition among the individuals of the same species. Its focus on population is also essential to Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Although many may find it surprising, Darwin initially shared a view common among biologists at the time that species in the wild produce only as many progeny as can survive. Malthus’ observations on man helped to shape his view of living organisms in general, especially the struggle for existence within and between species. This way, Darwin realized that death must be a non-random, and therefore selective, force.

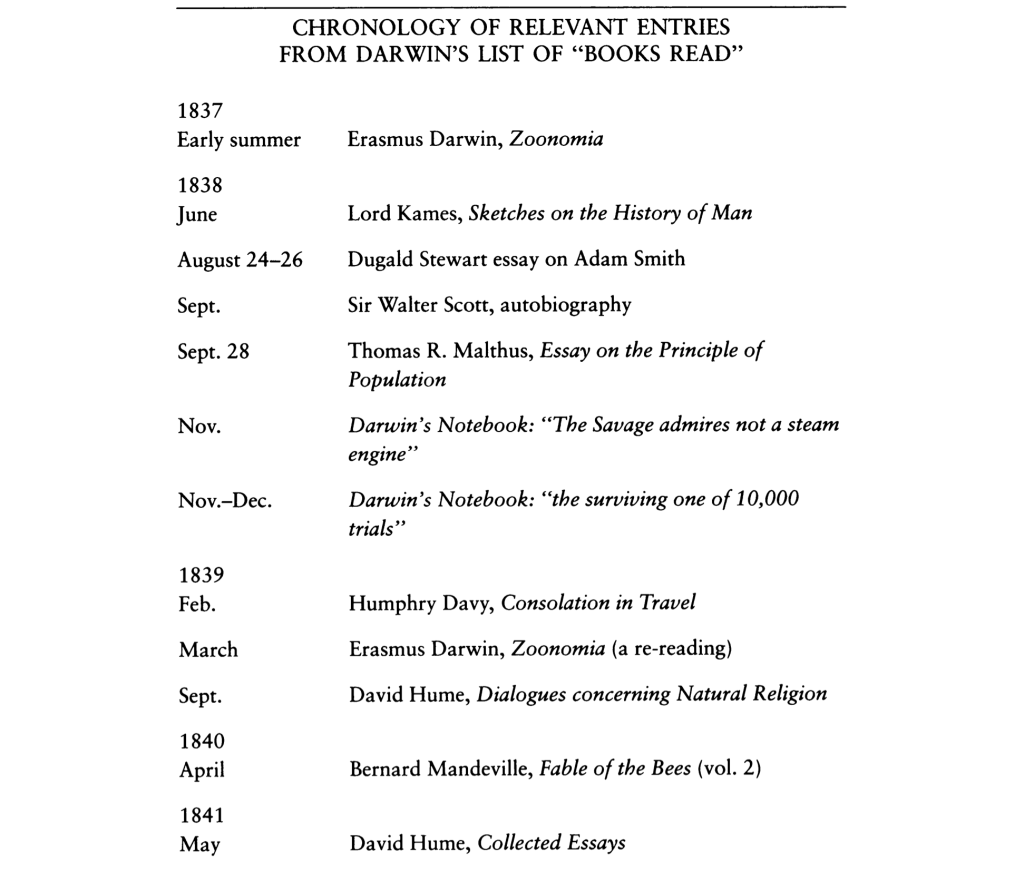

Darwin was unfortunate to live before the best website on the Internet was created, so he had to write down all the books he was interested in by hand.

(Source: Alter, 2008)

The Plural Perspectives and My Conclusions

The purpose of this post was not to answer the provocative question contained in its title. The aim was to show that the visions of competition described in classical political economy and the scientific theory of evolution are interdependent. Just as Darwin gained significantly from studying the work of early economists, so 21st-century economics has much to gain from examining Darwin’s evolutionary theory. Perhaps the most essential benefit of this is that she reflects on the discipline’s forgotten roots. A feature of classical political economy clearly presented in this post is its interdisciplinarity. It allowed the work of economic thinkers to inspire biology decades later, leading to the discipline’s most remarkable scientific theory. Mandeville’s works on the reliance of social order on individual actions opened Darwin’s eyes to the idea of emergence. Thanks to Hume and his reflections on morality, he understood how natural instincts can contribute to the development of social cooperation without intelligent design. Smith’s industrial analysis of the division of labor, illustrated with a pin factory, led to the formula of biodiversity. And Malthus, describing the problems of demography, anticipated the studies on natural selection. As Karl Marx summarized it best: “It is remarkable how Darwin rediscovers, among the beasts and plants, the society of England with its division of labor, competition, opening up of new markets, ‘inventions’ and Malthusian’ struggle for existence.’”

Classical political economy encompassed wide-ranging studies from moral philosophy to market competition, but its intellectual influence did not stem solely from its interdisciplinarity. It was also a movement that dared to criticize established conventions, such as trade policy or the social system. Classical political economists, despite the risks involved, openly opposed both the protectionism postulated by mercantilists and the absolute monarchy praised by the physiocrats. Despite its revolutionary mission, early modern economics remained both self-critical and cautious. Openly admitting that her research aims to improve society’s situation, she is at the same time careful to apply theoretical considerations directly to public policies. In the writings of economists from this period, we find numerous references to the opinions of their predecessors. Sometimes the ones approved, sometimes the ones criticized, and sometimes the ones mentioned only to present a different perspective. It was the pluralism of perspectives that classical political economy recognized as the best path to understanding a complex economy.

I have read with great interest (more than once) both articles applying complexity science to competition law published in 2023 and mentioned at the beginning of this post. From the perspective of the above considerations, the relationship between these two papers becomes particularly intriguing. Nicolas Petit and Thibault Schrepel refer to Darwin as a precursor of complexity science and try to follow his direction with tools of evolutionary economics focused on dynamics. Ioannis Lianos takes a critical approach to the contemporary mainstream of economics. Still, his subsequent research on complex adaptive systems is, to a large degree, based on a turn to political economy. In this post, I suggest that these approaches do not lead in different directions and, although somewhat distant, remain parallel. This seems to confirm my belief in the still-untapped potential of combining evolutionary studies and political economy. The differences between these two approaches to “complexity-minded competition policy” prove that it’s no longer just a movement advocating for the start of debate, but already a field of discussion. I believe that the multitude of perspectives it presents will inspire further research that leads to a better understanding of competitive processes in a complex economy.

Cover: Bank of England £10 note (Charles Darwin) & Bank of England £20 note (Adam Smith) (artwork by Julia Graczyk @juliagraczyk.illustration)

Leave a comment