CLEP – The interconnected challenges of the 21st-century global economy necessitate a reevaluation of competition law systems worldwide in the spirit of multidisciplinarity. It means not only reviewing in light of its intellectual roots in jurisprudence, microeconomics, and ethics, but also recognizing the rapidly increasing number of valuable insights from contemporary studies on information and complexity. This blog post marks the beginning of the Competition Law, Economics, and Philosophy series, which will comment on this process. It will be a mix of these three disciplines, seasoned with a bit of literature, science, technology, and personal experience.

Science (Fiction) of Competition

Computational Antitrust, Neal Stephenson, and Benford’s Law

Note: This blog post attempts to convey as much as possible about the usefulness of Benford’s Law in the context of computational antitrust within its short length, while minimizing spoilers of Stephenson’s book plots.

File: SSRN

My favourite part of working in academia is getting to know people with wide-ranging interests. I do not only mean those of my colleagues who have combined expertise in many areas of competition law, ranging from its early history to its ongoing practice. What I’m writing about is their interest in different disciplines, hobbies, and even sports. Listening to them talk about their activities is so absorbing because one can often hear in these stories curiosity and reflectiveness, so characteristic of scholars. Obviously, it’s also a good way to gain a deeper understanding of your own career by learning about others’ motivations and inspirations. It appears that the community of competition law, comprising experts with interdisciplinary backgrounds in jurisprudence, economics, and ethics, attracts individuals who are not only T-shaped lawyers but also multipotential individuals.

The 2024 ‘Power in a Digitalized World and Modern Bigness’ conference at the University of Utrecht may have been the first time I was introduced to Neal Stephenson‘s work. It is one of many proofs of how inspiring their competition law team is in many areas. There are many reasons for us, researchers, to reach for the author’s novels. Presenting Stephenson’s silhouette isn’t the aim of this blog post. However, it is still necessary to do justice to his achievements, which are closest to contemporary concerns of our discipline, in a few sentences. Inspirations derived from sci-fi literature aren’t that rare in competition law literature. One can easily find references to works by authors as diverse as Asimov, Matheson, and Vonnegut. The genre is not so much an attempt to predict the future, but rather a way to picture the way we imagine, and frequently fear, it. However, Stephenson succeeded more than once in the former endeavour. He is not only a writer but also a professional futurologist (for historical reasons, I prefer this name to ‘futurist’), whose novels combine both these calls. What’s crucial in this context is that his 90s projections focused on the economic changes to be brought by the digital revolution.

The 1992 Snow Crash introduced the concept of ‘Metaverse,’ an idea that has evolved gradually since then and recently gained significant momentum due to Meta‘s massive investments in this area. Additionally, the novel’s background is characterized by competition in various markets, ranging from pizza delivery to fiber optics. As a character, L. Bob Rife, “last of the nineteenth-century monopolists,” complains, “a monopolist’s work is never done. No such thing as a perfect monopoly.” Seems like you can never get that last one-tenth of one percent.” Still, he doesn’t worry much about competition law. He adds, “Watching government regulators trying to keep up with the world is my favorite sport” (p. 105-106). The essential 21st-century shift that competition authorities must keep up with, to fulfil their role, is the advancement in computational techniques.

According to Publishers Weekly, the 1999 Cryptonomicon is “often credited with sketching the basis for cryptocurrency.” At some point, “Stephenson had to publicly deny the (mostly tongue-in-cheek) rumor that he might in fact be Satoshi Nakamoto, the mysterious creator of Bitcoin” (The Baffler, 2022). The novel is an international thriller of spies and codes, spanning from the Second World War to late 20th-century cryptography undertakings. Its importance for competition law and economics doesn’t arise only from the increasing interest in blockchain observed within the discipline (e.g., Schrepel, 2021 & Stylianou, 2025). It is simply because both competing and enforcing competition law are, to a high degree, about code-breaking. This blog post aims to illustrate the statement with a single example of computational antitrust techniques. I plan to develop this perspective in the coming CLES texts, mainly inspired by Hayekian understanding of “competition as a discovery procedure.”

Stephenson’s work is influential at the highest levels of (big) technology companies, the same ones that so often raise concerns of competition authorities nowadays. Bill Gates, Sergey Brin, John Carmack, and Peter Thiel are all fans of his work. In the early 2000s, he worked for seven years as a part-time advisor to Blue Origin, the spaceflight company founded by Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon. His role focused on “novel alternate approaches to space, alternate propulsion systems, and business models.” The Snow Crash concept of the Metaverse inspired the inventors of Google Earth. The book was also a required reading on the Xbox development team under Microsoft executive J. Allard. However, in this brief blog post, I’d like to highlight his more recent work, one that at first sight seems less rewarding as a read for competition lawyers and economists trying to understand the digital economy and computational antitrust.

The 2008 genre-crushing Anathem starts with a note to the reader explaining that “the scene in which this book is set is not Earth, but a planet called Arbre that is similar to Earth in many ways.” As a novel of ideas, it addresses various philosophical problems. Still, it’s clear from the beginning that its central themes are the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics and the debate between Platonic realism and nominalism. The reappearing question is about the impact idea(l)s have on the reality we directly experience. As an individual trying to know as little as possible about the plots I’m about to read and choosing them based mainly on recommendations (thanks, Emil!), I feel personally responsible for avoiding spoilers at any cost. Therefore, I limit myself to sketching the novel’s setting and, please forgive me, mentioning one historical event of the universe. The Arbre, year 3689 AR, is a world where theory and practice are separated. Around the planet, mathematicians, scientists, and philosophers live in walled cloisters, which they leave only once in a decade, century, or even millennium (depending on their rank). The “extramuros” doesn’t bother much about the sanctuaries crowded with hermits. When in need, the powers that be have the right to evoke one of them when in special need of her knowledge.

Evoking a scholar is a rare event on Arbre. Even the political elite outside the cloisters doesn’t recognize the work done within them as applicable to its aims. A significant part of this stems from the fact that isolated scientists distance themselves not only from external events but also from most widespread technologies. Their research primarily utilizes ink and substitutes even paper with leaves. Outsiders often imagine them as just “prancing around with butterfly nets or looking at shapes in the clouds” (p. 48, which is an apparent reference to Aristophanes’ comedy). The Arbre history knows only one event that made the theoretical advantage of the secluded sages admirable enough to call for a meeting of representatives from all the cloisters around the planet. In 1107 AR, the detection of a dangerous asteroid approaching the planet forced all to admit that cosmographic theories, which relied heavily on naked-eye observations of the sky (what an irony), might be the only hope of saving the whole of Arbre. While the idea of computational antitrust is primarily based on the application of advanced technologies, this blog post aims to demonstrate that even mathematical theorizing itself can support significant advancements in this area.

The so-called ‘computational antitrust‘ may be the most innovative research initiative in our discipline at present. Some of the leading authors refer to it differently as ‘data-driven competition law‘ or ‘more technological approach.’ Another name for it, ‘Antitrust 3.0,’ suggests its revolutionary character, marking the beginning of a new era after the Political (1.0) and Economic (2.0) epochs of this legal system. Regardless of the name used in their specific research, most authors would likely agree with the general definition of computational antitrust as “a new domain of legal informatics which seeks to develop computational methods for the automation of antitrust procedures and the improvement of antitrust analysis” (Schrepel, 2021). For some, it might be an ignotum per ignotius definition; making it accessible requires explaining two of the supposedly explanatory terms. Legal informatics applies the science of data processing for storage and retrieval (information science) and computational techniques associated with emerging technologies to the field of legal practice. Computation is “the action of mathematical calculation,” usually done with “the use of computers,” understood as “an electronic device for storing and processing data, typically in binary form, according to instructions given to it in a variable program” (Oxford Languages).

Computational antitrust is a response to various ongoing and interlinked processes that make the global economy more complex and dynamic. Market entities are already making effective use of computational techniques (both for competitive and anticompetitive purposes), but “[t]here is a significant informational gap between the structure of antitrust agencies and the fast moving business world” (Jin, Zokol & Wagman, 2022). According to Ashby’s Law of Requisite Complexity, “If software supports a complex organisation, its complexity must match the complexity of the organisation” (Rzevski, 2023). Acknowledging that markets exhibit every characteristic of a “complex organisation,” and competition law often serves as its “software,” we reach the conclusion that to stay in the game, the legal system needs to increase its complexity through evolution by forming new computational links with the available data sets.

One of the most developed techniques in the toolkit of competition antitrust at the moment is data screening. Its “tools in competition investigations are empirical methods that use digital datasets to evaluate markets and firms’ behaviour in them, identify patterns and draw conclusions based on specific tested parameters” (OECD, 2022). The screening methodology is relatively easy to explain. It is of great importance, as the integration of computational antitrust tools into the process of law enforcement will significantly rely on their interpretability and accessibility for judges and policymakers, many of them without economic and (more often) an information science background. Screening can greatly support early detection procedures by identifying patterns in the data that are anomalous or highly improbable (Abrantes-Metz and Bajari, 2012). I find it especially interesting that screens don’t have to be based on price, cost, and information; they can also make use of abstract mathematical laws, such as the one introduced by Robert Benford in his 1938 paper ‘The Law of Anomalous Numbers.’

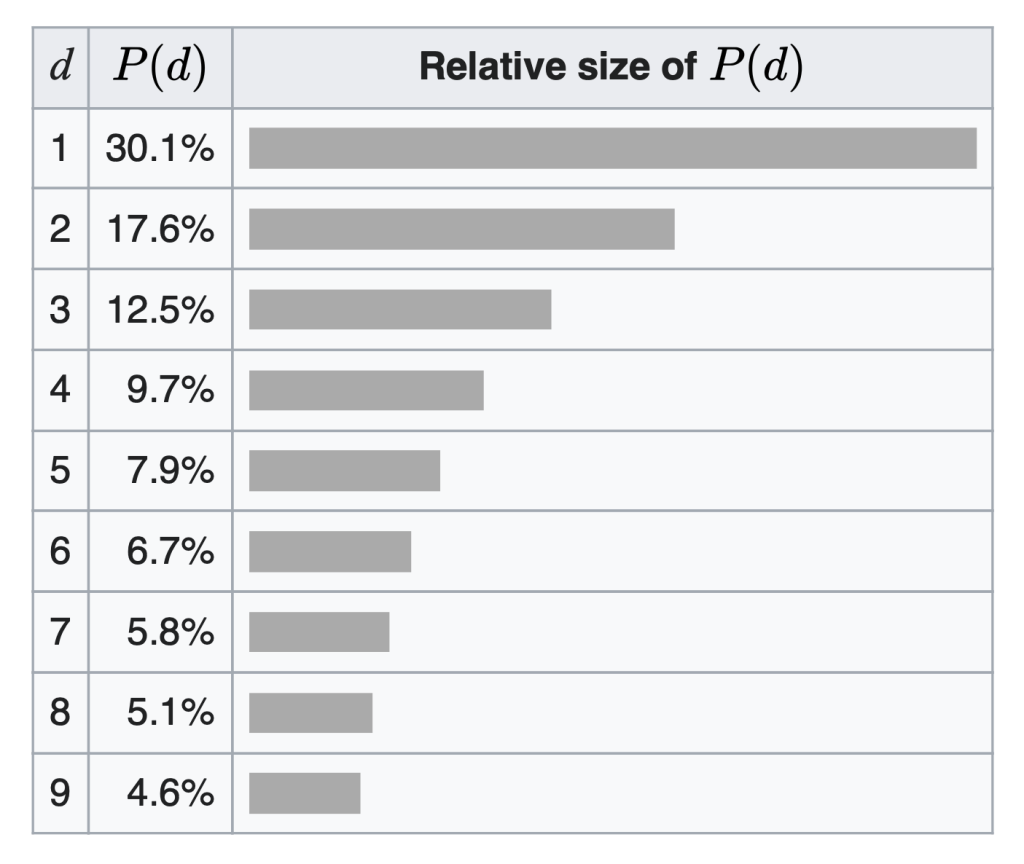

Beware. This paragraph is about to introduce what is sometimes called “the most counter-intuitive law” in mathematics. Fortunately, even if the statement is correct, the law is at least very easy to explain. Benford’s Law is an observation that in many real-life sets of numerical data, the leading digit is likely to be small. In other words, the share of numbers starting with a specific digit in a real-world dataset decreases as the value of the digit increases. Here is where the most interesting part begins. This observation is not only correct for the large majority of these sets, but most of them also have a distribution of leading digits very close to the pattern calculated by Benford based on his extensive research in the 1930s (he has tested it on data from twenty different domains – the surface areas of 335 rivers, the sizes of 3259 US populations, 104 physical constants, 1800 molecular weights, 5000 entries from a mathematical handbook, 308 numbers contained in an issue of Reader’s Digest, and the street addresses of the first 342 persons listed in American Men of Science).

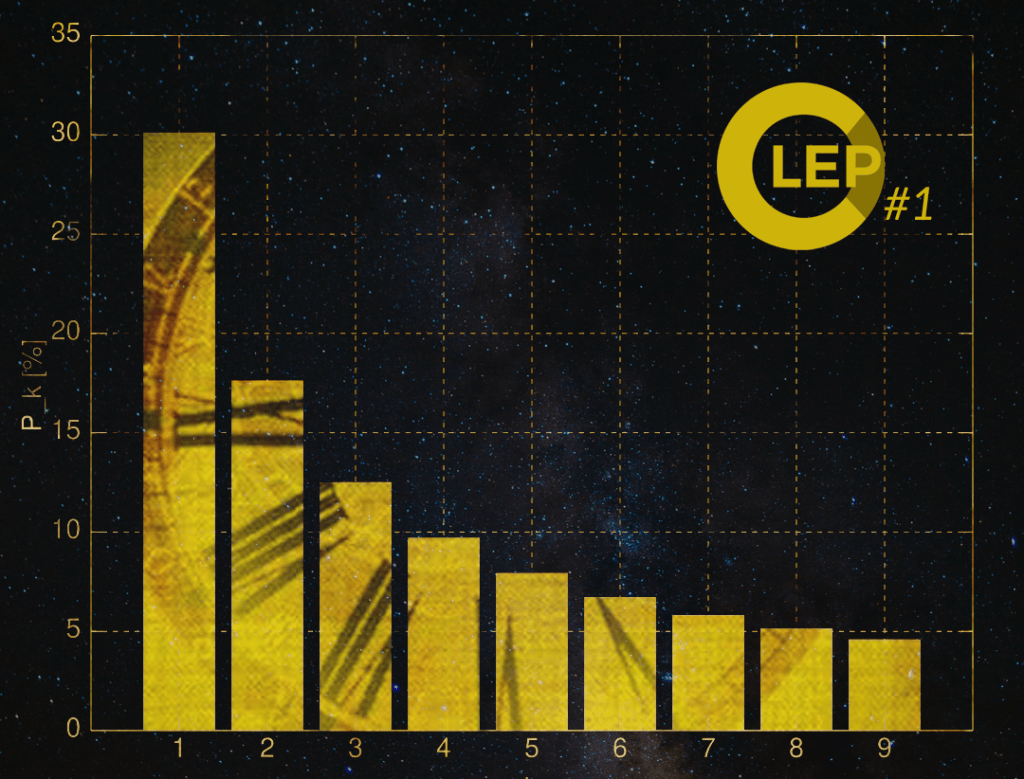

Graph 1: The distribution of first digits, according to Benford’s law

k = the value of a digit

P_k [%] = share of numbers starting with a digit in real-life data sets

Source: Wikipedia

At this point, one should give justice to Simon Newcomb, Canadian-American astronomer, applied mathematician, and autodidactic polymath, who reached the same conclusions already in 1881, a few years before the emergence of antitrust. It means Stigler’s law of eponymy applies in this case (proposed by statistician Jospeh S., not to be mistaken with his University of Chicago colleague, and economist of enormous importance to competition law, George Stigler).

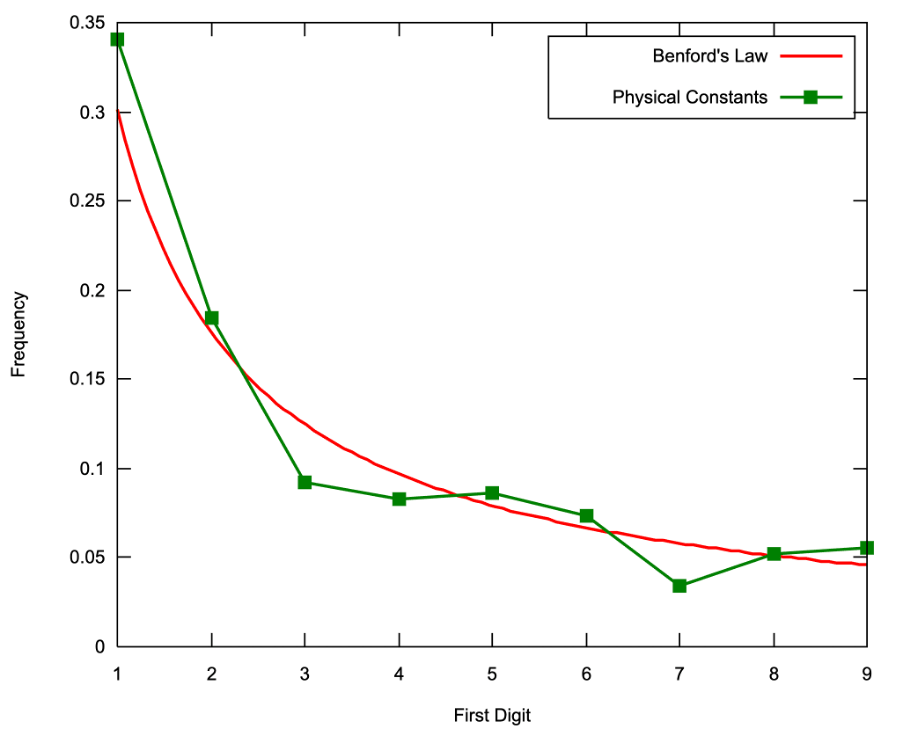

(Newcomb-)Benford’s Law tends to be most accurate when values are distributed across multiple orders of magnitude, primarily if the process generating the numbers is described by a power law (which is common in nature). Obviously, it generally applies more accurately to large data sets with numerous observations as well. Still, even relatively small sets like one holding values of crucial physical constants show stunning similarity to the pattern.

Graph 2: Frequency of first significant digit of Physical Constants (n=104) plotted against Benford’s law

Source: Wikipedia

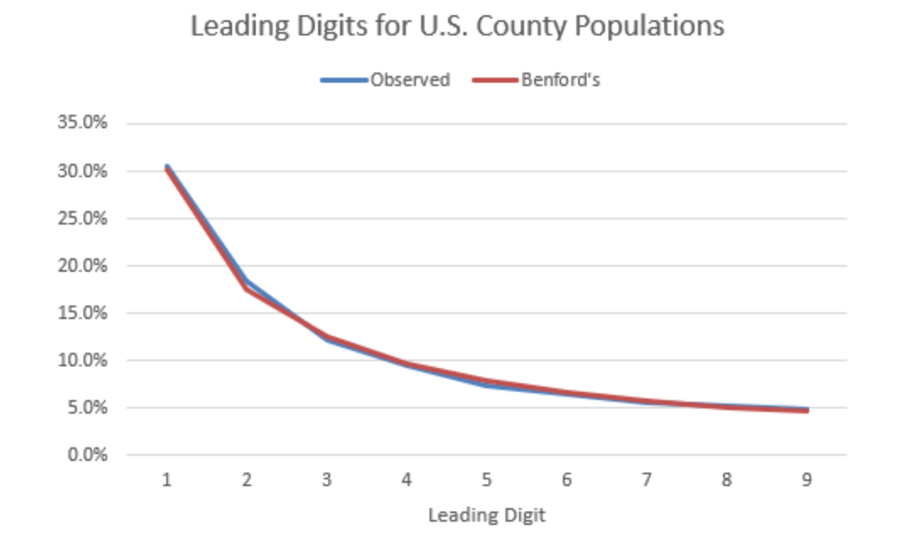

When applied to extensive datasets, the correlation with the pattern is often hard to believe. The collected values of the U.S. counties’ populations are an example.

Graph 3: Frequency of first digit of U.S. County Populations (n=1,344) plotted against Benford’s law

Source: (Alebbadi, 2023)

Ok, one may find it interesting. However, the question remains: what does it have to do with computational antitrust? I assume that, at this point, many readers can come up with an answer on their own. Since a strong correlation with the pattern described by Benford’s Law is universal, its violation suggests that the data may have been manipulated. Hal Varian had already suggested it in his 1972 letter to the editors of The American Statistician. Around that time, auditors began successfully employing it in screening to detect fraud and manipulation in accounting data. One of the first applications of data screening based on Benford’s Law in the context of competition law arose from the infamous “Libor Scandal.” In short, the European Commission imposed in 2013 the record sanction of almost 1,5 billion euros on a cartel of eight international financial institutions manipulating the pricing process of the Libor and Euribor benchmark interest rates, distorting the competition in the underlying trading of interest rate derivatives (financial products of value at least 800 trillion euros). The collusion was revealed mainly thanks to the leniency program. In 2011, two years before the decision, Abrantes-Metz, Villas-Boas, and Judge analyzed data on Libor using a second-digit distribution variant of Benford’s Law. As they discovered, over an extended period, the benchmark interest rates departed significantly from the mathematical pattern, suggesting data manipulation. As summarized by Danilo Sama, on whose 2014 text this paragraph is based, “through a quick application of the test, the Libor cartel could have been discovered much time before the opening of the settlement procedure.”

Seminal research by Abrantes-Metz (2011) led to a spillover of knowledge on the usefulness of Benford’s Law among competition law and economics scholars around the world. Rauch, Goettscheb, El Mouaaouyb, and Geidelb (2013) used this mathematical pattern as a basis for screening the behavioral trends of Western Australian petroleum retailers from 2004 to 2012. Their analysis shows that “price data featuring a low level of conformity with Benford’s law go along with suspicious patterns resulting from the other indicators of collusion” (e.g., smaller price-cost correlation or higher average margin). An area of collusion, especially well-studied since then, with the use of screening based on mathematical observations, is bid rigging (Robertson and Fleiß, 2024). It is because bidding markets, in comparison to other markets, are much more transparent and offer a large amount of publicly available data to screen. This market activity is therefore of importance to the development of computational antitrust, as a systemic review of case studies by Amthauer, Fleiß, Guggi, and Robertson (2023) argues that methods applied in previous investigations may be transferable to other types of infringements. However, this transfer is contingent upon an increase in the complexity of the competition law enforcement system, which can result only from new computational links with useful databases.

Screening data on market conduct using Benford’s Law is a basic yet accurate and robust method, which has already contributed significantly to the development of early detection procedures in competition law enforcement. Unfortunately, it’s just as easy for competition authorities to use screens based on this mathematical observation as it is for entities impeding the economic process to catch up by keeping it in mind when manipulating data, and avoiding detection on this basis. However, producing false data with a focus on respecting the real-life appearance of Benford’s Law might cause the emergence of different anomalous patterns. Even if cartelists and abusers learn mathematics as well as competition authorities, it still might give an advantage to the latter. The example of screening based on specific mathematical observations demonstrates that the work of “government regulators trying to keep up with the world” is a challenging task, and overtaking market entities in this race is nearly impossible, even in the short term. The near future will reveal whether those foreseeing computational antitrust as a necessary step in the evolution of competition law possess futurologist skills comparable to those of an acclaimed writer from Seattle.

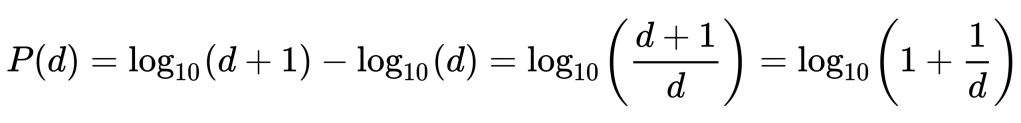

Appendix – Benford’s Law mathematical definition

A set of numbers is said to satisfy Benford’s law if the leading digit d(d ∈ {1, …, 9}) occurs with probability:

The leading digits in such a set thus have the following distribution:

Source: Wikipedia

Cover: Benford’s Law graph (Wikipedia) & Neal Stephenson, Anathem [Atlantic Books 2008 edition; ISBN: 9781843549154] (artwork by Julia Graczyk @juliagraczyk.illustration)

Leave a comment